Gender, age, and lifestyle can adversely impact client ranges of motion, flexibility, and/or safe biomechanics. Poor pandemic postures may, unfortunately, add to chronic issues which impede activities of daily life (ADL) and athletic performance. Fitness professionals can and should address these mobility and flexibility issues and prioritize senior stretching skills when working with this population. Here’s how personal trainers may judiciously factor skillful stretching into their regimens for senior clients.

Trainers should be prepared to address complements between stretching and movement exercises with clients, such as:

- Is a Sun Salutation yoga series considered to be “stretching” or is it an “exercise”?

- Is a World’s Greatest Stretch (below) also an exercise of dynamic sequences?

- Are Self-myofascial Release (SMR) techniques and Foam Roller stretching, or considered to be some other function?

One means to address the semantics is to encourage clients to think of intersected motives for flexibility, stretching, and warmup/cooldown.

Stretching in Theory and in Practice

With isotonic movement, our muscles and connective tissues sense and respond with our central nervous system (CNS). At some individual timed point of fiber lengthening, our protective CNS may responsively signal the muscle fibers with a “myotatic reflex” to limit further lengthening.

With skilled, “longer” time-stretching, we can condition our CNS to overlook that myotatic reflex signal and continue lengthening fiber. Practical limits to a range of motion (ROM), discomfort/pain, or soreness will likely occur for many seniors in their key body regions (Figure 1).

Functional Assessments for Range of Motion (ROM) are important precursors to a Trainer’s effective stretching regimens for these “trouble regions”.

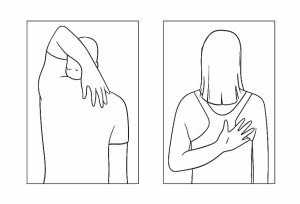

One of many useful assessments is the Apley “scratch” test (shown here) to check a client’s shoulder mobility and ROM:

Another is the Thomas Test to subjectively assess a client’s hip flexors and core ROM (Psoas muscle group). From a practical lifestyle vantage, our aging clients can and should invest time to maintain or to improve their “fitness ages.” A client’s performance in two formal tests of fitness age:

Sit-Reach (shown here)

Sit-Reach (shown here)- Walking Speed is unquestionably linked to prolonged flexibility

- Skilled stretching.

As Scientific American offered in its special edition, Secrets of Staying Young (March 2015),

“Regular prolonged movement—at whatever intensity level can be safely managed—

needs to be built into everyone’s daily habits and physical environments.”

Older clients who are flexible and supple in ranges of motion can often manage higher levels of activity to enhance their quality of life. Note: We must be mindful of occasions when stretching is not appropriate for some clients at select times:

- Osteoporosis or limited joint stability.

- Experience of sharp pain with joint movement or muscle elongation.

- Recent bone fracture, joint sprain, or muscle strain.

- Hypermobility.

- Inflammation in or around a joint.

A National Institutes of Health report offers two more practical considerations for bespoken stretching efforts:

- Most static stretching training studies show an increase in ROM due to an increase in stretch tolerance (ability to withstand more stretching force), not extensibility (increased muscle length).

- The effectiveness of the type of stretching seems to be related to age and sex: men and older adults under 65 years respond better to contract-relax stretching, while women and older adults over 65 benefit more from static stretching.

Trainers should, therefore reflect on a client’s tolerance for getting close to a door of discomfort and consider both age, gender, plus lifestyle when they incorporate stretching and flexibility functions into clients’ sessions.

As an added practical reference, the older a client – the higher the percentage of individualized stretching to include in training progressions.

What (Generally) Works?

Raphael Bender’s meta-analysis in Stretching – What Works? nicely documents limits and temporal guidelines for lengthening:

- Static stretches (usually after a workout) are deemed most effective at about 30 seconds of lengthening for general populations

- The effectiveness of any modal stretch diminishes after about 15 minutes. (Fibers gradually return to their “resting lengths” in about 24 hours.)

- Total daily stretch time is more important than the duration of an individual stretch

- Improved ranges of motion (ROM) can be lost in about a month if stretching is not maintained

- Stretching can be equally effective for seniors in standing, sitting, and lying down starting positions

- Self-myofascial release (SMR) appears to work best in tandem followed-up with passive stretching moves.

- It is important to assess muscle imbalances; a short muscle will only increase in range of motion if its antagonist is adequately activated and strengthened.

A proper Stretching regimen should consider the client’s category of athletic focus, as evidenced in a 2014 Current Sports Medicine Report:

- Strength and Power

- Speed and Agility

- Endurance

In all three focus categories here, an athlete’s baseline flexibility is a dependent variable for What Works?

Also, combined stretching modes may offset or reverse detrimental effects of a singular stretch mode such as static stretching.

Based on most literature in this survey,

√ Static stretching rarely improved performance when done before an event, and may have instead hampered it.

√ Conversely, dynamic stretching before an event in the first two categories seemed to improve an athlete’s performance.

√ Endurance athletes did not realize performance gains from dynamic stretching before longer events in the cited literature.

√ Solely static stretching and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching are generally better for after-action and cool-down periods.

Metabolic Note: A minor “plus” for dynamic stretching is that it can burn about 6 dietary calories (KCAL) per minute of active stretching. Alternatively, static, passive stretching’s impact on a client’s metabolic rate is negligible.

Summary:

A benefits consensus is rare when one reviews literature for the type, timing, or combination of skillful stretching.

That stated: long-term lengthening of muscle fibers and improved ranges of joint motion are worthy effects of individualized, causal stretching regimens. As a client’s gender, age, and lifestyle factors are intrinsic variables for flexibility and range of motion, it is incumbent on personal trainers to identify what will work for each client.

Should a client ask, “Is it too late to start a stretching program?” author Yuriel Kaim advises:

“It’s never too late. If you are a senior looking to gain more independence, mobility, and flexibility, stretching just might be your new best friend…”

Let’s overcome pandemic posture, stretch and enable those new friendships.